Alex Weiser captures the dusky nights of New York immigrants

“in a dark blue night” tinges the experiences of Yiddish arrival and Weiser’s grandmother

New York composer Alex Weiser wasn’t a Yiddishist for most of his life. He grew up with New York Jewish heritage and culture, but Jewish topics would remain a dormant aspect of his intellectual pursuits for many years. Weiser studied music composition in college and after some years working in music administration, landed a job with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. This would spark a renaissance in his Jewish learning, which recently culminated in his album of compositions titled “in a dark blue night,” which was released on March 29.

After college, Weiser stayed musically active. “I was reading a lot of vocal music, and also chamber music,” said Weiser. Then his debut album, which set a number of poems in English and Yiddish, was commissioned by Roulette in 2019 and ended up being a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Music. Following this illustrious debut, Weiser received a commission from ASCAP which would eventually become “in a dark blue night,” which had its live premier back in 2021 before being recorded in 2022 and finally released this year.

Back when New York felt new

“in a dark blue night” is comprised of two sections. The first is the eponymous “in a dark blue night,” a setting of poems in Yiddish. The second is “Coney Island Days,” musical settings of oral accounts from the composer’s late grandmother Irene Weiser.

“in a dark blue night” centers the writings of Yiddish immigrant poets who settled in New York and particularly poems which describe New York at nighttime. The album’s liner notes include a conversation between Tenement Museum president Annie Polland and Niki Russ Federman, co-owner of the New York Jewish deli staple Russ & Daughters. Polland notes how the album “[brings] into relief the emotional experience of what it would have been like to encounter the city for the first time.”

The poets included Morris Rosenfeld who immigrated to New York in the 1880s, as well as Anna Margolin, Celia Dropkin, Naftali Gross and Reuben Iceland who all arrived soon after the year 1900. Today, everyone has some broad notion of New York culture, which has become central to our global one over the past century. But the New York these poets arrived in was still coming into itself.

The poets’ perceptions are conflicted, but all full of wonder. Where Margolin sees noise and tragedy, Gross sees the stars and illumination. Iceland feels the imposing nature of New York’s gigantism while Dropkin describes a sharp contrast, describing an idyllic land of honey created by the labor and similitude of worker bees.

Aside from being in Yiddish, none of the poems actually touch on Jewish themes directly. Maybe this reflected the renegotiation of identity each poet had to engage with. Just as with New York broadly, Jewish New York (which today has many identifiable markers) was, just as well, only coming into itself at the time.

Matching these distinctions, Weiser’s compositions are emotionally nuanced. They follow a tradition of art song, creating unique sonic worlds to pay heed to each poet’s words. “My credo, so to speak, in setting poetry to music, is that I really try to bring the poetry alive in its own terms,” says Weiser. At the same time, the songs are blurry and impressionistic, capturing the terrifying majesty the poets describe and maybe even the uncertainty of our memories today.

Weiser’s intricate uses of timbre, voicing and countermelody underneath relatively straightforward harmonic modalities reflect this. Just as early New York may have had a clarity in the simple majesty of its illuminated modernist and art deco buildings, each poet (along with Weiser) seemed to know there was much more to it as they were learning to fit into this new city, increasingly at the center of a brave new world.

Snapshots of Coney Island

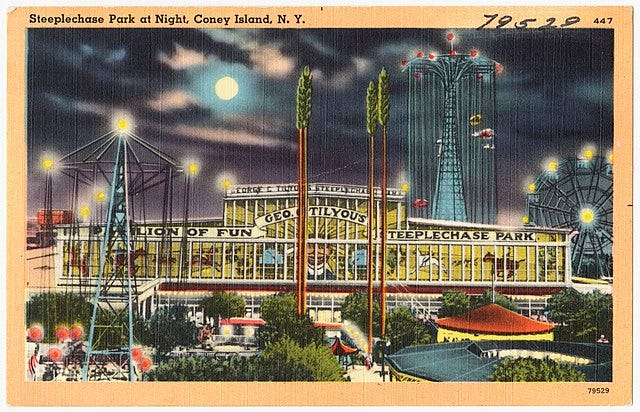

In “Coney Island Days,” Weiser leans on accounts from his late grandmother, Irene Weiser as the source material for his songs. Federman notes in the liner notes that “there was very often a feeling among the immigrant population that their own stories were not that important. It wasn’t shame, exactly, but the idea that their family history wasn’t interesting.” While the poets give us intricate emotional portraits of New York, Irene Weiser’s stories are straightforward recollections, the gorgeous, honest kind anyone’s grandparent might give of their childhood.

They are descriptions of simple joys, realities and circumstances of the time, especially reflecting trips to the famous amusements at Coney Island. To match, Weiser’s compositions in this section touch on oom-pah flavors and recognizable structures that feel more proletarian and easier to pin down while still remaining in Weiser’s refined compositional style.

New York then, New York now

Reflecting on the album and its place in the evolution of Jewish culture, Weiser returned to Federman’s restaurant Russ & Daughters, who have remained popular by evolving to do modern takes on classic New York Jewish cuisine, as a corollary.

“I see the work that I'm trying to do as being a similar thing [to Russ & Daughters], but with music. I'm trying to go to the source — this amazing, incredible Yiddish poetry from the turn of the century and these personal stories from my grandmother — but then to package them in this really elegant and very contemporary way.”